There is an expression out there that goes something like “When there is a solar energy spill, it’s just called a nice day.” This is in obvious contrast to oil spills (killing wild life and making a general mess of things) or nuclear melt downs (killing everything and poisoning entire areas for centuries). At this point I suspect I may be a bit biased, but no matter how you look at it a nice day beats ruining things every time.

This is the story of how and why I got solar panels on my house. It’s been something I’d considered for years and years and never did anything about. Let’s face the truth here, it’s a lot of work, a lot of research and a lot of money. I’m all for saving the environment where I can, but solar panels are super expensive and a bit over the top for even the most tree-hugging of folks.

A few years back, my dad got solar panels on his house. He explained the process and the costs to me and I started thinking about it all over again. And I didn’t go through with it again. Even with all of the potential government rebates and potential savings on my electric bill, I was still scared to consider the expensive modification to my house that is solar panels. After the following years of my dad enjoying his panels and his lower electric bills, I had enough evidence that they were something to seriously consider.

That started the official research phase for getting solar panels. I started researching everything I could find. First I looked at government rebates. The federal government had a great plan where I would get 30% of the cost of the system back as a tax credit. (Not to be confused with a tax deduction.) This was a good start because it essentially means that I would pay 30% less thanks to that program. Then I started looking into whether or not Connecticut would help out too. As it turns out, they will, but in a vastly less impressive way than my dad enjoyed in New York. (He got a system that was 40% bigger than mine and I paid twice as much as him. Most of that difference was the size of the state rebate programs.)

Once I figured out how much I could save, the next part was to figure out how much it would cost. This started me down the road of researching three separate solar companies. I chose a local guy, the company my dad went with, and SolarCity. This spawned a lot of research into how solar stuff works. It would obviously be tricky to understand the various offerings of each solar company if I didn’t understand what they were offering in the first place. As it turns out, there was a lot I already understood about solar, but there are a lot of ways to do each individual part, and the differences between those ways were what I didn’t fully understand. To read up on what makes up a solar system and how it all works together, head over to my How Solar Works post. It’s a bit too long to include here.

The first differences I started to notice between the installers was their overall responsiveness to my questions and how they dealt with me on the phone. I suppose that’s not exactly a part of how various solar systems differ, but let’s face the truth here these are people I am going to have to deal with a lot. If your installer can’t provide you with accurate answers or doesn’t understand your questions you may want to look elsewhere. Even if you only deal with your solar installer for the amount of time involved in actually getting the system installed, it’ll still be a rather long time. Best case you have a reasonably long warranty period and the company you deal with continues to exist for the whole time, so you should definitely trust them and enjoy dealing with them.

After installers I started asking about the panels themselves. You may simply assume that any roof covered in pretty bluish black solar panels has the same basic thing up there but in reality not all panels are created equal. They have different efficiency ratings (how much of the sun they can capture and turn into electricity, typically expressed as a percentage like 12% or 18%), different degrade rates (all panels get less awesome over time, the slower they do so the better, also typically expressed as a percentage but more like 1.0%/year). Beyond that they have factoids about which country they were made in, how many watts they can put out, and how they can be mounted to your house. All of these things should be carefully considered too.

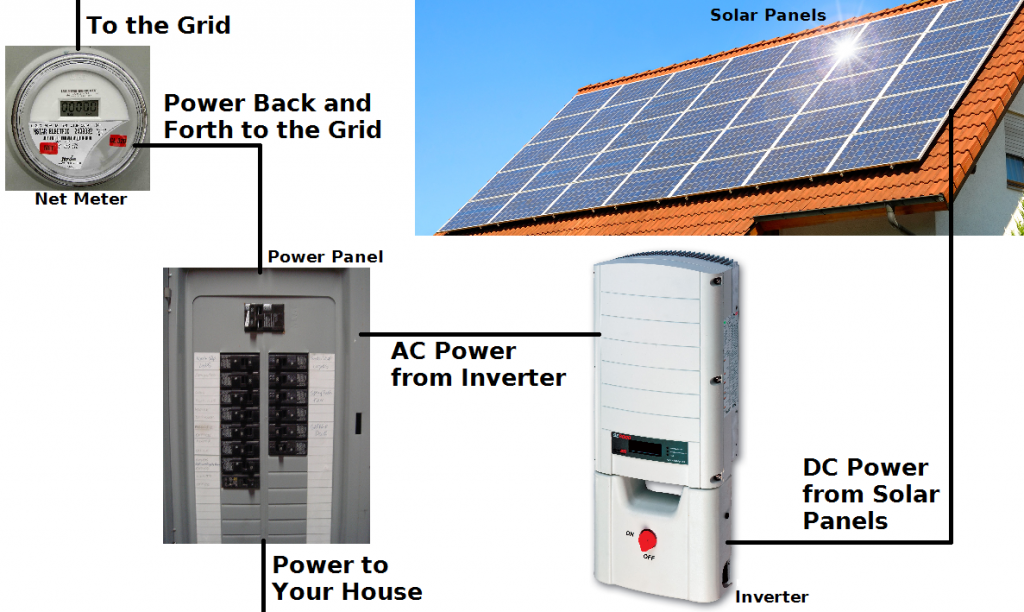

With loads of answers from solar installers that clearly had no idea what they were talking about when I was asking the harder questions, I moved on to the different arrangements of inverters. After all, solar power for your house wouldn’t be of much use if your house can’t use that power. The three major arrangements I discovered for inverters were single inverter, micro-inverters, and single inverter with micro-controllers.

Almost no one uses straight up single inverter any more because they are a disaster with things like shadows and dirt. Panels are typically wired in series and the whole group of panels in a “string” only operates at the level of the lowest producing panel. For example, let’s say you have 12 panels in a string and they are producing 250 watts each (3000 watts total). If a shadow from your chimney covers one panel and drops its output to 100 watts, all 11 remaining panels also drop to 100 watts (1200 watts total). That’s a huge loss considering the shadow is only over one panel.

Realizing this is a horrible arrangement, the solar industry came up with the idea of micro-inverters. Instead of one large inverter running your 12 panels in the example above, now you have a small inverter for every single panel (12 inverters total). Now that same shadow comes along and your one panel drops to 100 watts just like before. This time the other 11 panels continue to operate at 250 watts because they aren’t being dragged down by the under performing panel in the shadow. This means your 3000 watt system drops to a rather comfortable 2850 watts. This is obviously vastly superior performance to a single inverter system.

They realized that having one inverter for every panel meant that maintenance has the potential to be a bit of a pain, and that wiring all of your panels that way meant a bit more work to install as well. That is not to say that micro-inverters were a bad idea. They do keep a lot more of your panels working when one of them is having trouble, and that is really the goal. Then there was another idea. With a single inverter and small controllers for each panel a similar result can be achieved as with micro-inverters, but with the maintenance and installation complexity reduced back down to where it was before. The output of this arrangement with the same example as before would be the same 2850 watts as the micro-inverters produced. Overall, this is a win in my book.

Recently the added complexity of battery units attached to solar systems became something to consider. It is not however worth it in my opinion for several reasons. You don’t need it, it would have pretty limited uses, it’s expensive, and there are cheaper options.

You don’t need it because your extra solar power typically goes to the power company through your net meter in the form of a kilowatt-hour (kWh) bank. That means you are essentially using the electric company as a free battery, so why buy a battery that isn’t free?

Next, if you have a battery you can theoretically continue to use your solar panels even during a power failure. (Which is not the case in a normal system because you don’t want your solar panels electrocuting people working on power lines that they think have no power in them.) So in this case, the battery becomes a sort of generator for your house during power failures and would theoretically allow you to continue to use your solar panels in the case of a power failure.

The problem with this battery as a generator scenario is that a battery that can power your house for 12 to 24 hours (obviously depending on use) will run you about $7000. A gas generator that will do the same job for as long as you have fuel available will run you about $800. Sure you may have less maintenance on a battery and you may not have fuel handy when you need it for a gas generator, but how often do you really lose power? How many poorly maintained generators can you buy before you’ve covered the cost of a single battery?

So with all of these tidbits considered and researched it was time to get solar for myself. This story continues with the actual story of my own installation with SolarCity in the post From Zero to Solar (post is coming soon, not quite ready yet).